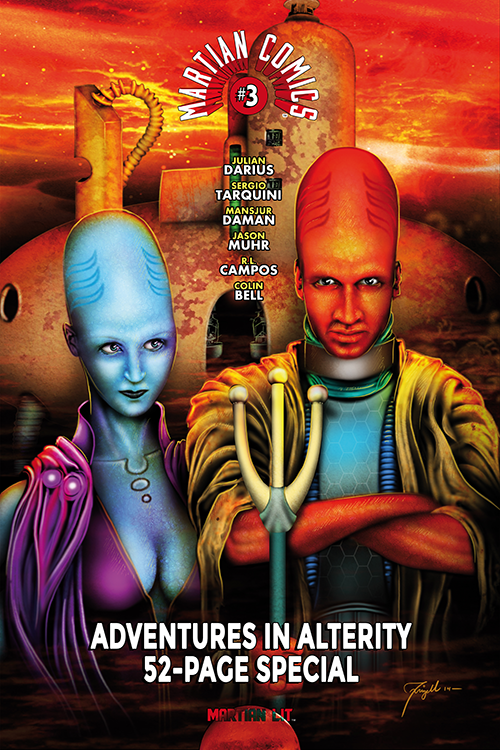

![]() This past month, Sacred and Sequential had the opportunity to chat with Julian Darius, President & Founder of the Sequart Organization and creator of Martian Comics from his own Martian Lit imprint. With the release of the Kickstarter-funded Martian Comics #3 and its intriguing religious content, he talks with us about the wide range of thinking behind his (not-so-)alien tales.

This past month, Sacred and Sequential had the opportunity to chat with Julian Darius, President & Founder of the Sequart Organization and creator of Martian Comics from his own Martian Lit imprint. With the release of the Kickstarter-funded Martian Comics #3 and its intriguing religious content, he talks with us about the wide range of thinking behind his (not-so-)alien tales.

S&S: Before we focus on the most recent Martian Comics #3, perhaps you could outline what “Martian Mythology” is and what was involved in producing these works?

JD: The “Martian mythology” is essentially the backstory of the whole series. Back when I founded Martian Lit, I thought it would be funny to have it actually run by Martians, and I worked up this backstory of planetary orders, an enlightenment program (that included Jesus and others), the cloaking of Mars’s cities, and the sort of vague threat that the Martians are still debating and split over whether to invade. There was a lot of detail for what was essentially a complex joke.

When Kevin Thurman pitched me on what became “The Girl from Mars,” it was wedded to this backstory I’d worked up for Martian Lit. As we collaborated on the early “Girl from Mars” chapters, I began expanding this backstory and writing these other Martian stories. It’s kept growing. It’s really because of this that the series is called Martian Comics — a throwback to titles like Adventure Comics and whatnot — and wasn’t titled The Girl from Mars. Initially, “Martian mythology” was a way of separating this backstory I’d created and was exploring in these side stories from “The Girl from Mars.” “Martian mythology” is kind of the backbone of the series — “The Girl from Mars” is the first story, the first window into that mythology.

But this “Martian mythology” has kept growing. There’s a map of stories waiting to be told, whole arcs of Martian history, ways in which themes echo throughout the stories and into the various more narrow stories, like “Girl from Mars.” It’s a pretty vast thing, which I’ve kind of put together over the past several years and keep adding to.

S&S: Let’s zoom in on a detail you mentioned there, how Jesus was part of a Martian “enlightenment program.” This is a callback to Martian Comics #1 and your story “The Galilean,” right?

JD: Right. The idea that Jesus was a Martian emissary goes back to that original backstory for Martian Lit. It was just in a parenthetical about how badly Earth has treated these emissaries sent to enlighten us. It was a bit of verbal cleverness, just kind of throwing this one emissary out there in this context. But once it’s established, it’s part of the mythology, and the mythology kept growing.

In the main “Girl from Mars” chapters of issue #1, the main character — apparently possessed by a Martian — is trying to explain this whole possession-and-enlightenment business to her sister, and she mentions Jesus. It’s a point in the conversation, a way for the main character to explain this concept. The sister says, basically, “If you’re trying to convince me you’re not crazy, it’s not a good idea to compare yourself Jesus.” And then the issue ends with this short comic that — surprise! — depicts this.

S&S: So, when we come to Martian Comics #3, two stories particularly stand out in terms of Sacred and Sequential’s concern with the intersections of religion and comics. The first, the short, 3-page piece “Ezekiel,” was named, presumably after the story’s protagonist, the prophet of the Old Testament. Was Ezekiel chosen for a particular reason? That is, it could have been Jacob’s angel revealed to be an alien or Obadiah’s Elijah. Is there something inherent to the story of Ezekiel that attached him to this story? Or is there the implication that any one — or all — of the prophets were similarly visited by extraterrestrial rather than divine presences?

JD: “Ezekiel” is only a three-page story, and it’s one of the first “Martian mythology” stories I wrote. The original idea was just to illustrate this earlier paradigm, in which Mars had visited Earth and exploited humans, prior to possessing humans as part of its softer “enlightenment” program. I’m not a fan of “ancient aliens” theories — I find them fascinating, but I’m repulsed by the idea that humans couldn’t build their own pyramids or figure things out on their own. That’s really a medieval, anti-Enlightenment notion, and I don’t want to perpetuate that — any more than the bare minimum, necessary for story purposes. One of the most famous “ancient aliens” theories is that Ezekiel’s “wheels” were alien spacecraft. I’d already written a short story in which Jesus was a Martian, part of the Martian enlightenment program, so it made sense to use Ezekiel to illustrate this earlier, more exploitative paradigm.

So that’s why it’s Ezekiel. As far as whether other prophets were similarly inspired, or which ones, that’s up to you to decide. I don’t think “Ezekiel” implies all prophets were inspired or directed in this way. However, there is this period of Martian history in which at least some Martians were doing this kind of commanding of humans. Those Martians were — quite reasonably — interpreted as divine by primitive peoples who were inclined to think gods governed anything they couldn’t understand, in a time when all human understanding about the natural world was far less than a grade-school child knows today. But exactly whom the Martians inspired or commanded like this, and the nuances of their agenda, I’ll mostly leave to readers to think about.

I did look at other Biblical prophets and other potential alien / angel encounters that I could explore. But part of the problem is that these prophets, at least in the Bible, are so obviously concerned with very local, tribal concerns that I can’t imagine an extraterrestrial caring about. We sometimes imagine extraterrestrials really caring about who’s elected president, or our various customs of dress or eating, and I don’t think that makes sense — those are transparently human values, bound to our particular concerns as humans grounded in a historical place and time and society. And the Bible is mostly so obviously — at least to me — bound in this way. There are a few counter-examples: Job is a searching metaphor for our relationship to power and the paradoxes of faith, and the Beatitudes are moving to me, although I’m a non-believer.

I also dig early Genesis, from a historical point of view — I wrote a master’s thesis on Milton, after all. But as cool as Eden is, there’s no Satan there, God simply isn’t omniscient (he can’t see where Adam and Eve are), and there’s no original sin as we understand it. What’s most remarkable is that almost everything we think we know about that story is provably wrong. That’s because we’ve been reading the retcons — this is something you and I have both talked about before — initiated by later versions of this story, and we’re taught them before we read the original, and we force these preconceptions onto the original in ways the text doesn’t support. We’re dealing with stories here, and those stories get revised over time.

So one problem I would have, were I to really focus on a prophet’s larger story, is that it’s hard to imagine that extraterrestrials would care. And that’s true of most of the Bible. I mean, it’s possible that an alien wanted to colonize or control a portion of Earth’s territory, and wanted humans to do it instead of just using alien technology, which would be much more efficient. And this might explain the astounding level of enthusiastic calls to genocide issued in the Bible — maybe aliens wouldn’t care about that, from a moral point of view. But it’s impossible for me to imagine the vast majority of the Bible as a moral document. It really isn’t, nor was it conceived that way — again, with rare exceptions. It’s a collection of stories, some poetry, and a mythologized version of a tribal history (which is fascinating to study, by the way). But it’s just not possible to imagine extraterrestrials inspired any of this for moral purposes, because there’s simply so little moral concern in the text. And there’s a weird predilection in the text for miracles, supernatural events that are more bizarrely chosen than impressive, and which usually work in an utterly immoral way. It’s like reading an early super-hero story, in which the hero summons a lightning bolt that kills some children, and you don’t know how to take that, and it’s pretty clear that the writer really just wanted you to say this was cool and that this hero is powerful, and didn’t want you to think more deeply about whether this made sense or was moral. That just wasn’t the point. I do think the Bible is fascinating, and you can see the way history weaves in and out of it, where the writers embellished and what they were reporting, how God evolves from a polytheistic, amoral being into a monotheistic one. It’s all right there in the text. But taking it literally and trying to square the circle by making a specific prophet’s life — at least, as recounted in the Bible — fit a specific set of Martians’ agendas (or a god’s agenda, for that matter) doesn’t seem like a particularly fruitful way to spend my time. I did try, around the time I was writing this story and afterward, when I was considering further Bible stories, but I realized it’s not something I want to do.

Like I said, I’m fascinated by the Bible, and I’ve written this kind of material before and will again. I live in the West and have degrees in literature, so the Bible’s kind of in my blood, both directly and by innumerable proxies. I keep going back to Biblical material, probably because I’ve spent so much time with it. But it’s not that fertile material, at least to my specific brain at this specific point in my life, for the Martian stories. Maybe another writer will come along and write a whole bunch more Martian Biblical stories focusing on the prophets, but it won’t be me.

I do understand that someone who’s a Muslim, a Christian, or a Jew might disagree with some of the above characterizations. And I want to be clear: I’m an atheist, but I’m not of the camp that religion is intrinsically evil, or is the cause of all war. There certainly are parts of the Bible that are moral, but it’s mostly a few lines here, a few lines there. Outside of Job, I don’t think there’s an entire book that’s concerned with moral questions, and it’s instructive to realize that Job is so ambiguous in its moral conclusions — or at least, so accepting of the fact that there are moral remainders. And there are certainly parts of the Bible that are immoral. The “no survivors” litany in Judges springs immediately to mind. But that’s not written as a moral document. We’re not supposed to question it, from a moral point of view. It really is just “our tribe is winning, praise God.” But I don’t consider the Bible — or religion, generally — to be immoral. I think it’s incorrect, to the best of our knowledge, and in places factually incorrect, but it’s not primarily a moral or immoral document.

Sure, we can ask moral questions of it, the same way we can of any story. But it’s like the Greek myth of Leda and the swan — you can question Zeus’s actions, but that’s not what the story’s about. It’s simply not designed to provoke that. You’re just supposed to accept that gods act like this, and it’s very much in the model of how powerful humans acted. If Europe had evolved worshipping Greek gods, we’d all see Leda and the swan as a moral parable, because we grew up with that framework and some very smart people devoted their lives to studying the story in that context, parsing out its mysteries. But there aren’t any mysteries, just ambiguities and tensions within the text.

Sure, we can ask moral questions of it, the same way we can of any story. But it’s like the Greek myth of Leda and the swan — you can question Zeus’s actions, but that’s not what the story’s about. It’s simply not designed to provoke that. You’re just supposed to accept that gods act like this, and it’s very much in the model of how powerful humans acted. If Europe had evolved worshipping Greek gods, we’d all see Leda and the swan as a moral parable, because we grew up with that framework and some very smart people devoted their lives to studying the story in that context, parsing out its mysteries. But there aren’t any mysteries, just ambiguities and tensions within the text.

All of this is just to say that I’m not personally inclined to focus on the prophets, either as people or as speakers of truth, the way you might be. For me, that’s not the point of this three-page story. The superficial point is to illustrate this more exploitative paradigm, of Martian-human relations. There’s also the exploration of the whole “Ezekiel’s wheels” idea, in which I’m juxtaposing (only slightly altered) Biblical text to images of a flying saucer and a Martian, and kind of trusting the reader to see how humans of that place and time might see this flying saucer differently and describe it in terms of their own paradigm. And of course, there’s this kind of eerie encounter between a primitive person and something truly other, something he can’t begin to understand, which I think is at the heart of the brief story.

To the extent that there’s a religious message, it’s really about power — about submission to religious authority. Because religion very much served that purpose, binding a people together despite ethnic and linguistic differences, but also binding them to their rulers — to the point that submission to divine authority is the primary “moral” lesson taught in these stories. For example, that’s the primary concern of the 10 Commandments, which really isn’t a moral document at all — it’s really about submitting to God, who is clearly primarily concerned with his own authority, in a very nervous and petty way. So that’s what’s going on in “Ezekiel” — this human is encountering something beyond his ability to understand, is interpreting it religiously and according to his own paradigm, and is submitting accordingly, because that was arguably the primary lesson of his religion, as it existed at that time.

S&S: Not only is the alien beyond his ability to understand; Ezekiel is awed by the presence of a genuine Martian: “This is the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord,” he recounts. What’s the message of this scene, of a biblical prophet coming to revere (as holy and divine) an alien visitor?

JD: Well, first, this is Ezekiel’s response to his visitation, in the Bible — it’s one of awe and submission. I didn’t make it up.

But it’s important, because it gets at this idea of the other and of different paradigms encountering one another. At the time, humanity essentially didn’t understand anything about the natural world. This was true even in ancient Greece, revered for its philosophical sophistication and for calculating the circumference of the planet (which of course, everyone educated already knew was round). It’s easy for us to fixate on the concept of the atom, but other Greek philosophers were far more interested in postulating about the four elements and whatnot. This was a time when you could still just make up what you thought stuff was made of, or how the body worked. There was a kind of logic at work, but it certainly wasn’t scientific. So again, we’ve got to understand that for 99.9% of humanity’s history, up until remarkably recently, even the smartest people understood far less than a grade schooler today. It’s hard to get our heads around this, but it’s true.

If you’ve ever been away from lights and the city, you’ve had the experience of looking up at the stars. It’s an awesome sight. It’s something spiritual, even to me. And we have to imagine that our ancestors did this, night after night, totally unaware of what these were, of why they were laid out like this — let alone that we orbited our sun. It didn’t take much to see that these stars rotated in the sky, relative to us, and societies all over the world charted them and found constellations — groups of stars that might be impossibly far apart in three-dimensional reality, but that looked like a group essentially orbiting in a giant sphere beyond the Earth. People all over the world named these constellations and saw their shapes as similar to things they knew around them. We literally projected ourselves onto the heavens, seeing men there — hunters, gods. People often thought the stars were themselves spirits. In the same way, they thought there were spirits of rivers, and that something divine ordained the rainfall. In culture after culture, religious authorities swore that such natural phenomena as rain were rewards or punishment for their behaviors — as if gods would be bothered to micromanage clouds and were really obsessed with whether someone committed adultery or whatever. It’s all absurd now, but it’s wonderful, in this primitive, magical way. And we lived like this throughout our history as a species — in an unknowable world, about which we were unfathomably ignorant from our current point of view, and in which divinities and magic alone seemed to grant certainty in a terribly uncertain world.

Obviously, science has done more to explain the world and the universe around us (and to liberate us personally, and to elevate our living conditions) than any religion or armchair philosopher. Humanity and its religions could tell an infinite amount of stories about the moon and contemplate its beauty and its meaning, but it was science that actually got us there. But it’s only been a blip at the very end of our history as a species that we’ve had writing, let alone science (as we currently think of that term). We evolved in a state of profound ignorance, in which the world around us was governed by magical thinking, and religions — among other things — provided maps to this magic.

Of course, it’s not quite this simple. There’s some evidence that our brains evolved as animists — that they’re inclined to see a rock as a separate thing, with a kind of beingness, and that we see the same thing in the movements of clouds and in animals and in each other, for evolutionary reasons. This may have helped us distinguish objects, and to value each others’ lives, but it also can’t be denied that we evolved in societies governed by magical thinking, in which this inclination in our brains wasn’t exactly discouraged. So I’m not saying religion was invented and made us think in this magical, incorrect way. It’s far more likely we’re inclined by our biology to look at the stars and not only to see patterns but to imagine some spirits at work, and every society we’ve found (to my knowledge) has some sort of spirituality, even if it’s shamanic leaders. There’s a lot of evidence that religions evolved from this pretty amoral shamanic tradition, and that religions only pretty late in their evolution start addressing morality and ethical questions. Until then, they’re a system of power and social cohesion, and offer answers satisfying to our innate desire to see things as having essences.

Now, let’s imagine someone with such a worldview encountering an extraterrestrial. He would have no ability to understand what he was seeing. He doesn’t understand that there are other planets, orbiting the sun, or even that Earth orbits the sun. He may not even have a concept of outer space as a vast three-dimensional place (which is very different than a series of spheres, for example). He doesn’t understand the concept of artificial flight, outside of the universal human desire to somehow be able to fly freely like the birds he sees, which was often attributed to supernatural beings. So he’s having a radical encounter with the Other, but he has no paradigm with which to understand this. He’s going to interpret these extraterrestrials and their spacecraft as mythological creatures, whether as giants or monsters who inhabit distant lands or as divinities — depending on his cultural specifics.

This is, incidentally, why dropping a microchip into the past wouldn’t produce a technological revolution. That’s a very silly idea, which really is magical. It presumes the microchip (or whatever piece of technology is involved) has a kind of essence, that it’s a sort of technological spirit, which would be reverse engineered. But people a century ago wouldn’t know what the hell a mircrochip was. You can imagine people thinking it was a decorative item — in fact, that’s how the ancients tended to interpret the potentially revolutionary science, like steam power, available to them. It was cool and great for trinkets, but its potential wasn’t recognized.

This same idea that we interpret things according to our own limited perspective is very dear to me, and it’s certainly not limited to religion or encounters. When I hear Republicans saying Muslims only respect strength, it’s obviously projection. Look at their foreign policy — it’s all ignorant bluster, sounding tough as if that has its own magical power that makes people back down. We all project like this, and it’s thematically what the projection tank in “The Girl from Mars” is all about. Really putting yourself in another point of view is very hard, if not impossible, and requires a lot of willingness to self-correct — but it’s the most reliable avenue to understanding another perspective.

This same idea that we interpret things according to our own limited perspective is very dear to me, and it’s certainly not limited to religion or encounters. When I hear Republicans saying Muslims only respect strength, it’s obviously projection. Look at their foreign policy — it’s all ignorant bluster, sounding tough as if that has its own magical power that makes people back down. We all project like this, and it’s thematically what the projection tank in “The Girl from Mars” is all about. Really putting yourself in another point of view is very hard, if not impossible, and requires a lot of willingness to self-correct — but it’s the most reliable avenue to understanding another perspective.

So part of the idea of Ezekiel interpreting the Martian as something divine is this idea — that he’s interpreting something utterly incomprehensible to him from his own paradigm. And of course, that’s an illustration of how limited his paradigm really is — and how limited all the paradigms of all our ancestors were.

But beyond this, there’s the idea I was talking about above, regarding the 10 Commandments. Throughout most of human history, we’ve lived under some form of theocracy. Obviously, the idea of separation of church and state was an Enlightenment one. And to be fair, there’s long been a distinction between the shamans and a tribe’s leader. But the leader is almost always said to be divinely invested in some way. It’s no coincidence that the 10 Commandments sound like the product of a very anxious, petty human dictator. It’s perhaps going too far to say that the dictator was a religious invention, but it’s key to understand that true totalitarianism doesn’t simply demand your obedience. It seeks to govern your thoughts and feelings too. It often governs what supposedly happens to you, after death. I’m tempted to say that nothing could be more evil — certainly, few things could be more damaging — than instilling guilt in people for normal human desires, like lust, and to furthermore convince people that this is not only surmountable through adequate faith but that one’s ability to do so will affect one’s afterlife. Talk about a recipe for twisted psyches and lifelong harm. But this is a key part of totalitarianism. And it’s essentially impossible without religion. Even in ostensibly secular totalitarian regimes, the regime co-opts the tools of religion and models itself after religion. Images of the Great Leader just replace those of God. And in the West, the model has very much been that jealous God of the Bible who could in theory issue those 10 Commandments, which could be considered by a very twisted mentality as a moral code but which are in fact the proclamations of a dictator concerned mostly with his own power.

Even Milton knew this. He was a great progressive in his time, but his argument against kings is based on the idea that earthly kings usurp God’s authority. Kingship was idolatry to him. Yet in Paradise Lost, you see that God is very much a tyrant, and it’s supposed to be fine. So even someone who opposed tyrants and monarchs did so because he thought God was an absolute monarch and had every right to be a tyrant. At least Milton took it upon himself to try to explain God’s reasoning, but even if you don’t understand or God was immoral and cruel, you were still supposed to obey. And that’s very much the presumption of the Bible, most of which doesn’t even entertain the notion that someone would question God’s morality. Obedience is supposed to be absolute.

So when Ezekiel’s response to the Martian is to kneel and to obey, he’s not only reflecting his own cultural paradigm, in which he’d interpret an extraterrestrial as a divine being. He’s also responding in a quintessentially religious way.

S&S: How did you and your artistic collaborator Sergio Tarquini come up with the character design for this ancient biblical figure?

JD: I don’t remember how much description I gave him. I tend to want ancients to be depicted as imperfect — as dirty, as missing teeth, as having scars. I don’t like this Hollywood effect, in which ancients look like present-day actors, with straight teeth and whatnot. I also don’t like depictions that are overly dominated by famous Renaissance depictions. I did look at multiple depictions of Ezekiel, in researching the story, but nothing stuck with me. But I don’t recall what instructions I gave him. I’m sure they were pretty minimal.

I tend to trust artists. If there’s something I really want in there, I’ll include it, and if I have a smart thought, I’ll put it in there. But I don’t tend to nitpick what they come up with. If something’s really off, I’ll point it out, but only after I consider whether it isn’t a legitimate artistic choice, or something I can work with.

So really, all credit for Ezekiel’s depiction is due to Sergio, and if there’s something amiss, it’s my fault for not putting it in the script. But I was happy with what he came up with, and I think it captures the spirit of what I was after.

(more to come in Part II)