Ever since I can remember, I’ve been a reader of comics. I grew up on the old Planet Comics black-and-white newsprint anthologies of DC titles before moving onto the more expensive and imported coloured individual issues of Marvel and DC from the US and the weekly issues of Tornado and 2000AD from the UK. Because I’d read anything in that format, I read various religious tracts and comics, as well as graphically-adapted works of classics like Jules Verne’s Mysterious Island or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and the serialised comics in the back of the daily newspaper.

Ever since I can remember, I’ve been a reader of comics. I grew up on the old Planet Comics black-and-white newsprint anthologies of DC titles before moving onto the more expensive and imported coloured individual issues of Marvel and DC from the US and the weekly issues of Tornado and 2000AD from the UK. Because I’d read anything in that format, I read various religious tracts and comics, as well as graphically-adapted works of classics like Jules Verne’s Mysterious Island or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and the serialised comics in the back of the daily newspaper.

I’ve always been intrigued by the power of these storied images, and as a Christian theologian with an interest in popular culture, I’ve spent the last twenty years or so collecting comics and graphic novels that have religious themes and material or touch on spiritual matters. Sometimes these comics are representations of sacred texts like the Hebrew or Christian scriptures; other times they explore themes of sacrifice, redemption, faith, and suffering. They might take an established comic book character and explore their religious dimension or fashion a detailed cosmology inclusive of heaven(s) and hell(s). There is something about the graphical format that lends itself to not just traditional narrative prose but also to poetry, to wordless stories, non-linear storytelling, and being able to tell stories from a variety of cultural and ethnic settings.

In these posts I’m going to highlight ten particular comic titles that I might recommend to people if they asked for examples of religion and spirituality in comics and graphic novels. I’ve deliberately steered away from graphical adaptations of religious texts like the Bible or material intended to educate or encourage the faithful. I may do a series on those eventually as they are also very interesting, but in these posts I want to highlight where we might find religion and spirituality in other contexts. I do not expect everyone (or anyone!) to agree with my choices, but I hope get you thinking about how people are telling religious and spiritual stories in this format.

1. Kingdom Come

- Publisher: DC Comics (1996)

- Writers: Mark Waid & Alex Ross

- Artist: Alex Ross

- Letterer: Todd Klein

- Publisher link: https://www.dccomics.com/comics?seriesid=429726#browse

- Wikipedia link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_Come_(comics)

Kingdom Come pretty much has everything you could want in a comic: Familiar characters recast by circumstance; conflict; an apocalyptic edge; great art; sacrifice, redemption, and hope; and excellent storytelling. It’s one of my go-to comics for showing people what a graphic novel or comic series should be like.

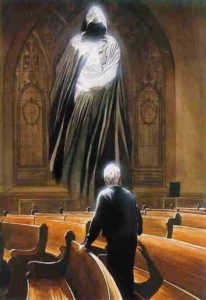

The story’s religious aspect, foreshadowed by the title, is lent to it by the story’s overarching apocalyptic premise. In a world of superheroes set the generation after Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman (who are seen as irrelevant or impotent now), the Spectre (God’s agent of vengeance in the universe, and a recurring character in the DC universe) confronts struggling pastor, Norman McCay, with the task of deciding the fate of the world. McCay narrates the story, coupled with apocalyptic visions he receives, and plays a critical role in story’s climax. The story ends with McCay recovering his faith and rebuilding a congregation with a message of hope.

Of course, the religious elements are not all that is going on here. There are questions about what true heroism looks like; ethical and moral dimensions played out through the characters and plot; the nature of (super)human relationships; and what hope looks like in a world that has lost it. As an Elseworlds title, it exists (mostly) outside of the canonical continuity, but its influence upon the shape of the DC canon is significant. And, of course, you get Waid and Ross’ brilliant storytelling and art.

Ross’ art is outstanding in this comic, capturing both the human elements and supernatural dimensions really well. If you like the style of Ross’ painted comic artwork, then I’d recommend Alex Ross’ Mythology: The DC Comics Art of Alex Ross. (It also has an interesting page or two exploring religious parallels between Superman, Moses and others.) There’s also a Marvel equivalent called of Ross’ work: Marvelocity: The Marvel Comics Art of Alex Ross.

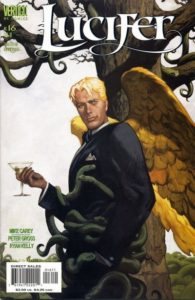

2. Lucifer

- Publisher: DC Comics (Vertigo imprint)

- Creators: Neil Gaiman; Sam Kieth; Mike Dringenberg

A comic about the Devil might not be to everyone’s liking, but DC/Vertigo’s Lucifer is located in a well-defined, imaginative theological and supernatural framework wrestling with free will, power, good, evil, and predestination.

The character of Lucifer (AKA Samael; Lucifer Morningstar; Satan; The Devil, The Adversary, etc.) first appeared in The Sandman #4 (April 1989) published by DC’s Vertigo imprint and created by Neil Gaiman. Drawing from Judeo-Christian texts and traditions, as well as wider mythologies, literature, and popular culture, Gaiman created a character that is far more complex than typical portraits of the Devil in popular culture.

Gaiman was doing something more than simply producing good comics stories on a monthly basis: he was also creating a work that aspired to stand as genuine, full-fledged mythology … But with Sandman, Gaiman aimed to use a comics-based mythos to expand on, interact with, and deepen classical legends of mythology and popular history. On one hand, this approach might seem like merely another clever postmodern ruse, taking old Greek and Norse myths, European and Asian and Islamic folk tales, plus scenarios from Dante, Blake, Milton, and Dore, and mixing them with 20th-century comics and horror elements. Still, Gaiman made it all work.

Gilmore, M. “Introduction.” In Sandman 10: The Wake, The Sandman, 8-11. New York: DC Comics, 1997. Cited in Porter, Adam. “Neil Gaiman’s Lucifer: Reconsidering Milton’s Satan.” Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 25, no. 2 (2013): 175-85.

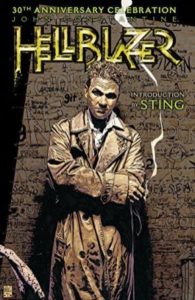

This complexity in both the characters and plots continued when others, such as Mike Carey, took over the writing duties through the 75-issue run of the comic titled Lucifer, and when the character appears in other Vertigo titles such as those concerning John Constantine (E.g. Hellblazer) and later spinoffs (e.g. The Sandman Presents).

If there is one consistent theme that runs through the Lucifer series, it’s the question of how much free will does one actually have in God’s plans. A common refrain is that it feels like Lucifer and others are exercising their free will to rebel against God or to abandon the ruling of Hell but how can they be sure it isn’t actually just foreordained by God. This forms part of the final conversation between Lucifer and God in issue #75 with the concluding thought being there comes a time when one needs to own who oneself is, to take responsibility for that, and then write one’s own story. In effect, it’s a kind of coming of age experience shaped by the existential crises brought about by wrestling with will, power, and destiny. (Philip Pullman’s conclusion to His Dark Materials books echoes this kind of conclusion).

Reading Lucifer is an interesting experience. Here’s the embodiment of evil, in a charming and often sympathetic portrayal. As a Christian theologian I bring a certain set of assumptions and commitments to reading this text; as a scholar of popular culture I bring others. As I read these comics, I’m constantly asking:

- How are sacred texts like the Bible, religious traditions and folklore, and wider literature and popular culture shaped into a coherent narrative and cosmology?

- How are the adherents of faiths like Christianity and Judaism portrayed in the stories?

- In what way do the stories evoke a sense of there being a spiritual or supernatural dimension to the everyday world replete with the presence of good and evil?

- In what ways are human characteristics projected onto supernatural entities?

- How are Heaven and Hell portrayed?

- How does this (graphical) interpretation shape how people, religious or otherwise, think about good and evil, the demonic and angelic, theodicy, the supernatural, and free will?

Recently, the character has been portrayed in TV series, Lucifer (2016-18) which has run for three seasons. There are moments when the depth of the comics turns up in the TV show, though different demands on a television show mean that there are less of those and more of comedy-drama police ‘buddy’ show. The casting of the central character may jar if you’ve encountered the comics previous. Apparently, Neil Gaiman was adamant that the comic book Lucifer was to be portrayed as David Bowie. So blond, somewhat gaunt, worldly-wise, and suave, and not the somewhat naive, dark-haired, and often impotent characterisation in the TV show.

Reading (or watching) Lucifer won’t be for everyone – it’s definitely aimed at a particular adult audience – but it’s worth studying because of the way it brings religion, the supernatural and comics together with complex characters, plots, and some quite deep questions. And so it sits at #2 on my list of religion and comics.

3. The Tithe

The Tithe is a criminal investigation comic that is framed within the pluralistic religious context of the contemporary US. Religion is present throughout the stories as part of the settings and plot the characters inhabit, but the focus of the story is primarily on the interaction of the central characters within that socio-religious context.

- Publisher: Image Comics

- Creator: Matt Hawkins

- First published: 2015

The Tithe is a police procedure drama that derives its name from its first story arc, Issues #1-4. In this opening story, a criminal group called The Samaritans are robbing a variety of mega-churches of millions of dollars (gifted through the religious tithing or giving of the faithful). Rather than keeping the money themselves, the robbers then donate the stolen money to charities.

The story’s protagonists are the two FBI agents who have been set the task of capturing the Samaritans, albeit without the support of the wider public who are enjoying seeing the rich pastors and evangelists, who are often involved in dodgy dealings with the money, getting their comeuppance. Dwayne Campbell is the experienced investigator, an African-American evangelical Christian, while the younger Jimmy Miller, an atheist, is the technical expert. This leads to ongoing conversations about faith, church, what worship is, and so on as they pursue the Samaritans. Eventually, circumstances escalate, someone gets killed in a robbery, the group is taken down, and the brains behind the unit, Samantha Copeland, is co-opted into the FBI team.

The second story arc, Islamophobia (Issues #5-8), deals with places of worship – Christian cathedrals and churches, Jewish synagogues, and Mormon temples – being the target of suspected Muslim suicide bombers. As the team investigate it becomes clear that the bombers were being blackmailed, with the entire thing is a set-up to make the US President look weak in the face of homeland Islamic terrorism and connected to white supremacist groups being used by a hard-line senator angling for a run at the presidency.

Again, it is the characters who make the story work. Campbell is wrestling with his daughter converting to Islam to marry and rejecting her father’s Christian faith, while Jimmy and Samantha become romantically entangled. Added to that is the fact that they know who is responsible for the attacks, but cannot get to him and are themselves in jeopardy. The story gives an unsettling story of how people’s actions and perspectives, religious or otherwise, can be manipulated to a point where facts cannot change their opinions.

The story continues in the third installment, The Tithe: Samaritan (Issues #1-3), along with a tie in to the series, Eden’s Fall, which connects it into a wider universe that includes Postal and Think Tank.

Apart from the fact that these comics are good stories, Hawkins adds in some nicely integrated biblical texts to frame the chapters, as well as including a section at the back of the comics that he calls his “Sunday School.” In the introduction to that, Hawkins gives some of his own journey from a Southern Baptist upbringing to his current atheism. The remainder of the “Sunday School” provides some information about the biblical text on tithing, how it’s often done in churches, as well as a bunch of links to similar scenarios around televangelist and mega-church scandals and various religious trivia. Hawkins’ also includes some letters, corrections to errors he made, and this comment.

At the end of the day, the comic is a US crime drama – it’s FBI or Criminal Minds or NCIS – which happens to be framed in religious contexts in a way that makes you think again about how religion and spirituality can function both positively and negatively in the world.