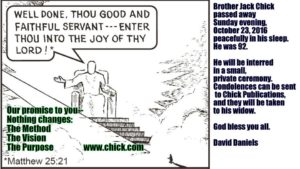

According to Chick Publications, their CEO and founder Jack T. Chick died peacefully in his sleep on Sunday night. He was 92. His death is mourned by some, and celebrated by others.

Since the news broke, “Jack Chick” has been trending on Twitter. It is not a pretty picture that is being presented. This is in no way surprising. For all but a select few, the man did not have a nice word to spare. And for the rest of us, he offered only glimpses of the hellfire that awaits us.

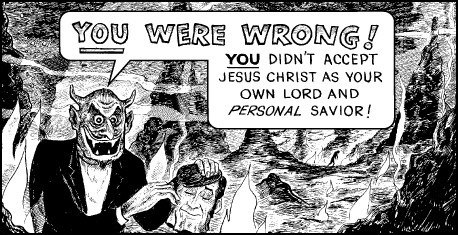

I should back up a bit, though, on the off chance that anybody visiting this site doesn’t know who Jack Chick was. He was the creator of the famous and notorious “Chick tracts,” small pamphlets containing black and white Evangelical fundamentalist propaganda comics. Chick had been publishing these pamphlets since the early 1960s, and his oeuvre touches on an impressive array of topics, from evolution to Halloween to “false religions” (everything that is not Protestantism, basically) to the end-times to, famously, role-playing games. The basic message was always the same, however: it doesn’t matter how good or bad you have been in your life, you are going to hell unless you accept the brand of Christianity that Chick promoted. You can read most of them here. He also produced comic books and sold literature that promoted his world-view.

The legacy he leaves behind is a strange one.

On the one hand, his work is often described as hate literature. It’s easy to see why this label is so readily applied. Anyone who differed from Chick’s in-group was condemned in the starkest of terms. Moreover, there were other aspects of his work that were just as objectionable. There were the racial caricatures. There was the separate series of “Black Tracts,” which consisted of variants of his standard tracts “adapted” for a black audience. There was the Islamophobia, the anti-Semitism, the homophobia, and the pumping up of fear among his readers that characterized almost all of his work. There was the recurring motif of murderers and criminals being let into heaven because they had accepted Jesus as their personal savior, while people who most of us would regard as more compassionate, relatable, deserving – “good,” in short – were shown going to Hell because they had failed to take the same step. And there was that one tract in which a porn-fancying father who is sexually abusing his daughter is talked into letting his neighbor do the same in order to keep the neighbor from telling the police.

On the one hand, his work is often described as hate literature. It’s easy to see why this label is so readily applied. Anyone who differed from Chick’s in-group was condemned in the starkest of terms. Moreover, there were other aspects of his work that were just as objectionable. There were the racial caricatures. There was the separate series of “Black Tracts,” which consisted of variants of his standard tracts “adapted” for a black audience. There was the Islamophobia, the anti-Semitism, the homophobia, and the pumping up of fear among his readers that characterized almost all of his work. There was the recurring motif of murderers and criminals being let into heaven because they had accepted Jesus as their personal savior, while people who most of us would regard as more compassionate, relatable, deserving – “good,” in short – were shown going to Hell because they had failed to take the same step. And there was that one tract in which a porn-fancying father who is sexually abusing his daughter is talked into letting his neighbor do the same in order to keep the neighbor from telling the police.

Let’s stick with this one a bit longer, because it shows just how deeply Chick stuck to his message. The daughter contracts herpes from the neighbor. When her doctor finds out, he confronts the father. Not about the sexual abuse, but about the sin and pornography. He convinces the father to accept Jesus. The father in turn convinces his wife – who had known about the abuse and had taken her frustration as herself a victim of similar abuse on the same daughter by hitting her – to also accept Jesus. The tract ends with the two of them telling their daughter that everything will now be well, because they love her, and so does Jesus. Everything about this tract is vile. The parents, the neighbor, and doctor all cry out for repercussions; they raped and abused the child, while the doctor is guilty of severe malpractice. But Chick wasn’t selling morals with his tracts, he was selling salvation. When we think of it in these terms, the tract is perfectly in keeping with his world-view and good summation of his larger agenda.

Let’s stick with this one a bit longer, because it shows just how deeply Chick stuck to his message. The daughter contracts herpes from the neighbor. When her doctor finds out, he confronts the father. Not about the sexual abuse, but about the sin and pornography. He convinces the father to accept Jesus. The father in turn convinces his wife – who had known about the abuse and had taken her frustration as herself a victim of similar abuse on the same daughter by hitting her – to also accept Jesus. The tract ends with the two of them telling their daughter that everything will now be well, because they love her, and so does Jesus. Everything about this tract is vile. The parents, the neighbor, and doctor all cry out for repercussions; they raped and abused the child, while the doctor is guilty of severe malpractice. But Chick wasn’t selling morals with his tracts, he was selling salvation. When we think of it in these terms, the tract is perfectly in keeping with his world-view and good summation of his larger agenda.

I would love to go into a few finer points here, to note that for Chick, for example, his work was not hate literature, but a form of “love literature.” Or to discuss in more depth how the division between “us” and “them” that he erects between the so-called “Saved” and the “Lost” is provisional, which is the central point of his entire life’s work; it only takes one small step to become like Chick and his followers. Or to compare his work to other forms of Evangelical “witnessing” or pop culture and show how, in important ways, he was actually not all that different or, as some atheists, many liberal Christians, and a whole host of others are so fond of claiming about Chick’s kind of overzealous religion, extreme. But those are thoughts for another day. For now, what I want you to take away from this first part is that Chick presented a world-view that, for many of us, is so alien as to be almost completely incomprehensible and that he did it in the hope of winning souls.

On the other hand, Chick’s work has achieved a massive crossover success. It is part of the Smithsonian’s permanent collection, as a slice of authentic Americana. It has spawned numerous parodies, some of which are directly anti-religious, while others are more generally satirical, and some of which play more on the fact that the tracts are so very, very recognizable. This is the case, for example, with the hit TV show Rick and Morty, which along with its season one Blu-Ray sent out tract titled The Good Morty. It has inspired a whole collector subculture, consisting of people from all over the world who, for one reason or another, can’t get enough of Chick’s tracts. Even those of us who are not Chick’s audience – in the sense that we don’t agree with him – who do not sympathize with his message, cannot look away. We share his work, we giggle, we condemn, and we keep looking for more.

Chick’s death, then, is a significant one in US comics history and in the history of US religion more generally. Thanks to the efforts of missionaries, of collectors and fans, and of scholars and critics and journalists, he had by the time of his death become one of the world’s most widely distributed cartoonists, if not the most widely distributed, as religion scholar Darby Orcutt claims in A. David Lewis and Christine Hoff-Kraemer’s Graven Images. He has shown in such an incredibly palpable way that, despite fundamentalism time and again being called medieval and despite fundamentalist’s claims to reject the outside world, it is modern and that it does interact in concrete and (in a sense) productive ways with its surroundings. Halloween is fast approaching, and with that comes Chick Publication’s annual campaign to get people to drop Chick Tracts in trick-or-treaters’ bags instead of candy. The outreach and resultant crossover success of Chick’s work forcefully illustrates the mismatch between two different ways of seeing the world, as well as the tension and conflict it can engender, both in how outraged many have been with his message and in the interest it keeps holdinThe g for so many of us.

I have written about Chick before, and I have had a book about him in the works for a while now. In fact, I had been working on Chick-related material just an hour or so before I heard the news, a piece about how his work can serve as a bridge to understanding fundamentalism as something ordinary. When I read about his death, I knew I had to write something that went beyond those first notices I saw, that were just a characterization or two of Chick as a vile man and a few paragraphs pasted from his Wikipedia page. His work deserves serious attention, even though he might not deserve our sympathy. From the moment I opened up my word processor to write, I struggled with what tone to strike in this piece. Part of me wanted to jump on the bandwagon and rip him apart for all the pain he has caused. Part of me wanted to try and stay as close to objective as I could. Maybe even try and find the good in him. I chose neither, and instead wrote what you see before you, a blend of both that fails as either kind of text. I’m not glad he’s dead. I’m not going to speculate about what revelations he has become privy to since Sunday night. But I’m also not going to mourn his passing. If you can’t say anything nice, the old adage goes, don’t say anything at all.

Again, I can’t do either and remain intellectually honest, so instead I leave you with this: Jack T. Chick died on Sunday, October 23, 2016. He is mourned by some and heckled by others. It’s the end of an era, for good and, to a lesser, and in a far more complicated way, ill.

Really interesting, Martin, thanks. I knew nothing about Chick, and now I can’t wait for your book! Good luck with it!

Mario,

thanks for your kind words and encouragement! I’m sure that there will be a notice here once the book’s starting to come together, so you’ll know when it grows near.

As a post-script:

http://www.comicsbeat.com/31-days-of-halloween-jack-chicks-halloween-comics-and-his-photo-verified/

I applaud the urge to balance a report on something like this, Martin. Your considered thoughts on these tracts are a useful and needed point of view. I want to register my own unease, too. That is, formally and business-wise, Chick was brilliant. Those recognizable strong graphics are some of the most elegant in comics. The format is the right size, shape, and feel for the purpose. The marketing plan has unquestionably gotten the tracts into hands for decades— whether or not I believe the numbers that Chick Publications puts out.

However, my own praise here feels— as you understand in your article here— uncomfortably like praising the train schedule during Hitler’s regime. The content is often actual hate speech more strongly than even the examples you give. Beyond the fact that I— as an educated woman who is also a professional biblical scholar— have seen myself portrayed as one of the many legions Jack Chick condemns to eternal torment, I am wary of any praise to a set of texts that is successful in so far as it convinces people of picture of Christianity I find offensive. It incites people to hatred and actions against the groups mentioned above, often already vulnerable groups regularly victimized by others. The Southern Poverty Law Center and the Canadian government are two groups that I understand to have called these hate speech. It’s a marketing marvel, but what do we do when hate is done well? In my own work, I often run across comics whose form or initiative I’m dying to support, but whose content is unpalatable sometimes to the point of turning even my strong stomach. It’s a problem I’d love to continue to discuss. How can we be scholars to not just anti-heroes but actual villains? In short, I can’t wait to read your book on all this!

Thank you for your comments!

It’s easy to be uneasy with this material, and I completely understand how you feel about it. I do feel that if we are ever to properly assess Chick’s importance and impact – and I cannot think anything but that he has had a profound one – as a fixture of both the evangelical landscape and of US pop culture more broadly for half a century, study must start out in an attempt to understand where he was coming from.

Like you, I belong to several of the groups that Chick has condemned over the years. The first time I ever came across him was in the early 2000s, when a friend handed me a copy of the D&D tract on a night when we were going to play an RPG, and from there he has come back time and time again. If we play the label game, I would have to self-describe as an atheist, and I have actively and explicitly rebuked offers to “get saved” (“Do you know what means?,” I was asked after one of those attempts, and immediately thought of Chick.) My intention is not to praise Chick or his work; to be absolutely clear here, I personally find both utterly reprehensible. But professionally, I cannot let the off-hand “hate literature” dismissal sit. I cannot be content with dismissing it as missives from the lunatic fringe that presents an extreme and inauthentic image of evangelical Protestantism. In many ways, Chick’s work was in continuity with Protestant history and with contemporary US evangelicalism in both ideas (in contents) and in forms (in his choice of medium, in his rhetorical strategies, in his arguments, and in how he presented his religion).

Have you read his tract “Who Cares?”, the one he put out just after 9/11? I’ve written about it elsewhere (http://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/who-cares-jack-t-chick-on-911). It does not directly incite hatred against a marginalized group – Muslims in this case – and, when read on its own terms, it is undoubtedly an expression of “love,” but in a way that, unless you accept Chick’s premises, is profoundly offensive. Do not do as others and victimize the Other, it urges, because – and this is the kicker – they might be convinced to convert. And they might do so precisely because they are commonly victimized. It is cynical, it’s exploitative, it IS hateful, but it is also perfectly in line with a particular, and for all we might want to think otherwise, relatively common, understanding of what “Christian love” is supposed to be.

From what I’ve read, I think Germany can be added to the list of people who have labeled Chick tracts as hate literature, although I have yet to confirm that. I do not protest the label itself, but I do think that if it is applied in scholarship on the works, we might be skewing our readings from the outset. And this is also how I think we can be scholars not just of anti-heroes, but of actual villains: we need to try, in our initial readings, to take the material on its own terms. It’s the same thing I always say about comics studies: to properly analyze and to reach plausible conclusions, the first step must be to place the material in its proper context and history. Evaluation can come after analysis, but it should never come before. It’s really hard, but it is necessary.