[The following piece was originally published at Women Write About Comics in two parts; and it is reposted here with the author’s permission, for the first time in its entirety.]

My cocktail party introduction of myself is basically, “I’m a religion scholar working on a dissertation that uses a comics to interpret religious text.” Maybe it’s not the smoothest handshake, but it’s a place to start. When I tell people this, I occasionally get quizzical looks from strangers who wonder how comics relate to religion at all. Either that or they are wondering if they are going to need another cocktail before we get into a conversation. The comics/religion relationship is a fantastic tangle that needs to be sorted out when we get into deep discussions. If we talk about religion and comics without sorting this out, we risk all kinds of misunderstandings and hurt feelings, not to mention frustrating cocktail parties.

Religion and comics have been in some sort of relationship for millennia. Stained glass church windows are a familiar Christian example; they tell the stories that are important to the builders of particular churches in different styles. Ancient peoples used comics-type language in cave paintings and Egyptian tombs to express their relationship to the supernatural. Although my own work centers mostly on Christian relationships to comics, I want to stress that there is much more out there to be discovered in comics from all the world’s religions. Comics are a medium that can deliver a particular message where text and images interact to create narrative and emotional results—something that religions of all stripes often strive to do and that comics can do with religious effect.

I conceive of the relationship between comics and religion in four categories: comics as religion, comics in religion, religion in comics, and religion and comics in dialogue. In this month’s installation, I’ll give you the first two categories (comics AS religion and comics IN religion), but be sure to follow along for the exciting conclusion soon. These categories are modeled on the four relationships between religion and popular culture more broadly as outlined in by Bruce David Forbes in his introduction to this great popular culture book with Jeffrey Mahan. They are solid tools for tackling a very messy relationship.

First, let’s tackle the rather fun comics as religion. Comics sometime function like a religion or religious text for their devotees. Thinking comics through religiously is pretty fun: the “fanboy” subculture with its rituals and festivals (like movie openings, comic conventions and Free Comic Book Day), moral and social codes (which when crossed cause “nerd rage”), temples (like comic book shops and gaming shops), and fetish objects (like certain first editions and even everyday comics that are kept sacrosanct, wrapped in protective layers). All this is ripe for scholarly investigation.

Comics often confront moral issues and prescribe moral codes and attitudes particularly toward nationalism, race, and women. There are many divergent views and ideologies in comics that play out in different comics, from tolerance and openness to racism and misogyny. These are fascinating books that begin to show just how much we can learn about ourselves through comics.

Sometimes this category makes practitioners uncomfortable on both sides of the equation. Religious people can resent scholars who compare religion too closely to popular culture fandom. Deeply committed religious people might find the idea that their worship or lifelong service to a higher cause is somehow like being a fanboy untenable. After all, comics have often been considered “lowbrow” entertainment. With this sort of reputation, even reasonable religious people might feel their views have been insulted if scholars aren’t careful. Comic books fans might feel uncomfortable thinking about what they do as religious. They might be devotees of a religion already and resent the idea that their hobby competes with their religion somehow, or they might have a negative view of religion. Popular culture scholars who think about religion deal with these sorts of issues all the time. Much of the controversy centers on what the definition of religion is that you hold, which could be the subject of a much longer article! In order to be heard and productive, scholars who think about comics as religion need to be respectful of these views and feelings as they study. By nature, good scholars of anything should strive to respect their subjects.

The second relationship, comics in religion refers to when religious groups produce or use comics or comics strategies for religious purposes. For a grand example see Amar Chitra Katha (ACK, Immortal Captivating Stories), a comic book series that has run in India since 1967 with the goal of educating the people of India about their cultural and religious heritage. This work is so pervasive that scholars tell me it has defined the popular understanding of gods and goddesses, historical events, and the canon of Indian myths and fables for whole generations.

Some of the earliest works that are recognizable as comics to the modern Western reader had Christian subjects. These early strips circulated on broadsheets, which have been studied from around the 1400s. David Kunzle’s work on the early comic strip shows the religious motives behind many of the earliest comics; comics might demonize the Pope, Martin Luther, or Jewish people in weird ways, warn against the hellish consequences of various vices, or simply extol or instruct in Christian virtues.

This long history of evangelism through comics can be followed from stained glass windows to the illustrated Bibles and printed by religious presses in the present day. Tracts, like those published by Jack T. Chick, are an example of comics used explicitly for religious purposes. “Chick Tracts”—now banned as “hate literature” in Canada—are illustrated pamphlets that aim to frighten readers into turning to true Christianity (and from particularly Catholicism and liberalism) with bombastic threats of hell-fire, damnation, and swift, violent death in a small-format, eye-catching design. Certainly there are other kinds of tracts, but with more than 500 million copies of Chick Tracts in circulation, they drown out any other Christian religious tracts that one might find. They are disturbing to the vast majority of people who identify as Christian. (See this funny video from Viga Loves Comics for a response.) There are many other comics in Sunday School curriculum, other types of Christian training, confirmation, and evangelism materials. Particularly, material for children, youth and for less-literate communities often contain not just illustrations but narrative juxtaposed images and text that easily fit the definition of comics.

Some comic books have been produced for explicitly religious purposes and with religious messages more or less out front. It makes for some pretty odd Archie comics. These moralizing and moralistic comics escaped much of the conflict and controversy around comics and the U.S. Comics trials of the 1950s. Although many groups who demonized comics (many of which were religiously-based) lumped all comics into the same ultra-violent morally bankrupt category, these comics were allowed a free pass. Educational comics, Archie comics, and Bible comics slid by the Comics Code Authorities with little trouble. Some comics benefit from the religious markets opened by their religious content. The Action Bible, for example, sells quite well to a children and teen audience despite its depictions of violence, sexual situations and troublesome behavior, because it’s found in the source material.

The other part of comics in religion are comics that may or may not be intended for religious purposes by their creators but that religious people put to religious uses. Comics usually afford this use through subject matter or themes. Whenever the Bible is in view, the comic naturally lends itself to religious reading, even if that was not the creator’s intent. R. Crumb’s The Book of Genesis Illustrated, though created by a man who “emphatically does not believe that the Bible is the word of God” and gained a reputation for sexually explicit work, nevertheless has been hailed in the religious magazine Christian Century as an aid to reading Genesis. Crumb’s opinion that “the idea that people for a couple of thousand years have taken this [book]so seriously seems completely insane and crazy, totally nuts” does not stop its potential for religious use.

This back and forth between religion and comics cause and effect makes figuring out when to name a phenomenon religion in comics and when to name it comics in religion difficult. When comics are brought into religious uses through whatever means by design or use, they participate in the comics in religion category. Of course, one comic can be studied from different perspectives and fit into multiple categories. That’s one reason it’s imperative that you all stay tuned for part two: religion in comics and religion and comics in dialogue.

In part one of this tangle, I talked about four ways I conceive of the relationship between comics and religion: comics as religion, comics in religion, religion in comics, and religion and comics in dialogue. In this month’s installation, I’ll give you second two categories (religion in comics and religion and comics in dialogue)—but be sure to back up and check out the way I introduce the whole thing in part one of this essay. (Bonus, I hint at my awkwardness at cocktail parties.

These categories are modeled on the four relationships between religion and popular culture more broadly as outlined in by Bruce David Forbes in his introduction to this great popular culture book with Jeffrey Mahan. The relationship is still tangled, but at least these categories help us sort out what we are talking about.

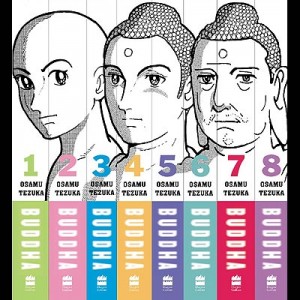

The category religion in comics encompasses comics that contain different expressions of religion. These first include comics that focus explicitly on religion and religious figures in a religious context such as Osamu Tezuka’s eight-volume series Buddha, an imaginative retelling of the entire life of Siddhartha, the foundational figure of Buddhism. The work acknowledges the religious context of Buddha without portraying the Buddha in a necessarily traditional way.

The category religion in comics encompasses comics that contain different expressions of religion. These first include comics that focus explicitly on religion and religious figures in a religious context such as Osamu Tezuka’s eight-volume series Buddha, an imaginative retelling of the entire life of Siddhartha, the foundational figure of Buddhism. The work acknowledges the religious context of Buddha without portraying the Buddha in a necessarily traditional way.

Second, there are comics that contain explicitly religious figures without focusing on their religious significance per se. This especially happens when religious figures are used for their unique stories rather than to offer a religious message. For example, the character of Thor in Marvel comics is a “god” in the comics, but the nature of his actual religious significance for German neo-pagan or different modern groups that practice modern Heathenry is hardly touched over the decades-long run. There’s been some awkward stuff recently in the Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D show that vaguely acknowledges contemporary religious groups, but that’s really a story for another time. Recently, the overdramatic guff over Thor’s powers going to a woman have made even more clear to even the casual fan that “Thor” in comics is a title and has only superficial things in common with his namesake. Thor controls thunder and certainly has human qualities, but hardly ever becomes a woman. (That’s Loki.)

Second, there are comics that contain explicitly religious figures without focusing on their religious significance per se. This especially happens when religious figures are used for their unique stories rather than to offer a religious message. For example, the character of Thor in Marvel comics is a “god” in the comics, but the nature of his actual religious significance for German neo-pagan or different modern groups that practice modern Heathenry is hardly touched over the decades-long run. There’s been some awkward stuff recently in the Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D show that vaguely acknowledges contemporary religious groups, but that’s really a story for another time. Recently, the overdramatic guff over Thor’s powers going to a woman have made even more clear to even the casual fan that “Thor” in comics is a title and has only superficial things in common with his namesake. Thor controls thunder and certainly has human qualities, but hardly ever becomes a woman. (That’s Loki.)

Above: Loki’s done this before.

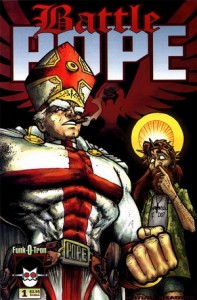

In putting religion in their comics, some comic artists do a kind of act of what philosopher Gerard Genette calls, “transvaluation”—taking characters down from their religious pedestals and giving them human qualities. For example, Jesus in the series Battle Pope is nothing more than the ne’er-do-well sidekick for the divinely super-powered, corrupt and lecherous pontiff.

In putting religion in their comics, some comic artists do a kind of act of what philosopher Gerard Genette calls, “transvaluation”—taking characters down from their religious pedestals and giving them human qualities. For example, Jesus in the series Battle Pope is nothing more than the ne’er-do-well sidekick for the divinely super-powered, corrupt and lecherous pontiff.

Yes, that’s Jesus picking his nose.

Battle Pope, by the way, is the brainchild of Robert Kirkman, now-famous creator of The Walking Dead. (Pick up his early stuff so you can say you knew him when.) Kirkman is hardly alone in the practice of transvaluation. Comic Book Religion, a site devoted to tracking the religious affiliations of characters in comics, has identified 166 distinct comic book appearances of Jesus Christ to date across multiple publishers and titles. Some of these are complimentary, but many are anything but! Reactions to the transvaluation of deities and important religious figures are, of course, mixed. Some people love seeing their own (or, more disturbingly, other people’s) religious figures mocked. Of course, it’s not always easy or possible to go along with the joke when it’s on you.

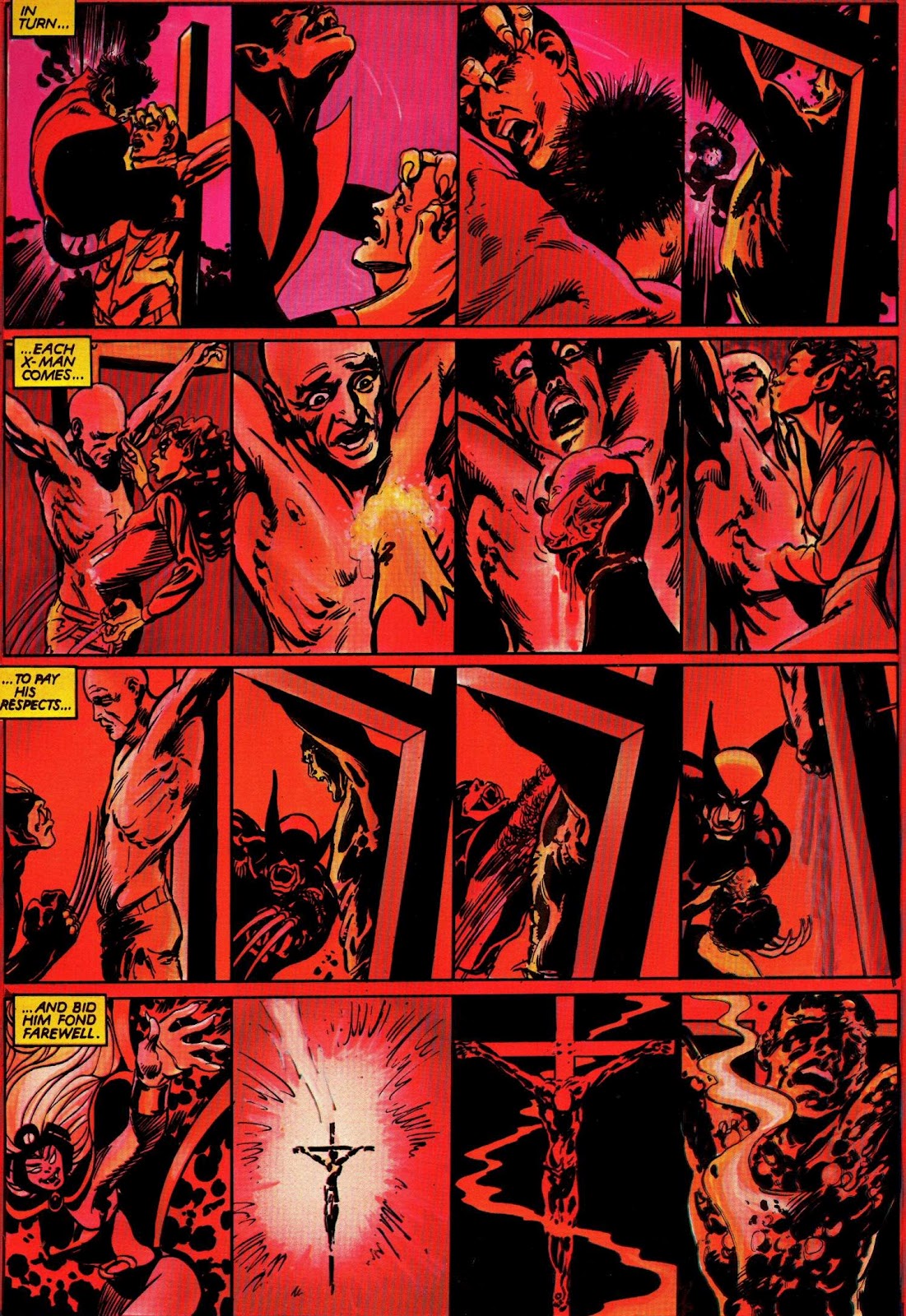

Comics also contain implicit references to religion. The most obvious and pervasive religious theme in superhero comics is a Christian trope—the “Christ figure.” That is, stories that use other characters, events, or images that recall or resemble the story of Jesus. Usually, they focus on the bit of the story where Jesus sacrifices himself to save everyone. Very few Christ figure superhero stories seem to focus on feeding people or fishing. Just not as flashy, I suppose, as something like the sacrificial Death of Superman. The interest in the phenomenon of Christ in spandex is widespread. Many scholars (including these, these and these) productively mine these works for their religious themes — whether the creators necessarily anticipated them or not.

Some comics that use Christ themes are obvious about what they are referring to, but don’t necessarily use them in ways the average reader might expect. In 1983, Chris Claremont and Brent Anderson created the classic X-men graphic novel called God Loves, Man Kills that connected the way a church-led organization crucifies the white male leader of the mutant X-men, Charles Xavier, and lynches two African American children. The fact that the children are also mutants does not blunt the political message or the emotional impact of the scene at all. There is no question that Claremont wishes the reader to recall Jesus and connect his suffering to both the children and Xavier; his caption at the start of the illustration of Xavier’s crucifixion is “And they bring him unto the place Golgotha… and they crucify him.” It’s an obvious quote of King James Bible rhetoric.

The position of religion here is ambiguous; the villain is a Christian leader, but the solution to the X-men’s problem ends up being religiously inspired as well. This is a moment when religion in comics begins to be religion and comics in dialogue.

Comics and religion cannot seem to stay away from each other. Because many comics are part of subculture, they get away with questioning powerful religious mores and figures in a way that films with their large budgets and political studios simply cannot afford to do. Of course, this has not been without consequences. The United States comics industry in particular has long suffered for its edgier elements. Often, loud voices of dissent about comics come from religious communities. This struggle is well documented in the book The Ten-Cent Plague. But, relative freedom of expression presents the opportunity for religion and comics to enter into dialogue.

Good Dialogue hardly ever involves burning things, unless we’re making s’mores and not using someone’s creative work as kindling.

This back-and-forth is not always respectful on either side, but the conflict is fascinating theatre. Religion can enter comics in a scandalous way—inspiring religious ire, pillorying mainstream religious mores or simply putting a twist on religious figures that are already established in the mainstream mind. This dialogue sometimes suffers from a deafening silence from both comics creators and religious people. While an offbeat retelling of a gospel comic like Markedenjoys the publication and marketing of a religion-affiliated press, the original story ofAmerican Jesus (or Chosen, depending on your version) languishes with only one volume completed. (Tell me more, Mark Millar, for the love of Pete.) Unfortunately, many religious people hardly touch the comics that directly transvalue their religious figures. They simply ignore them. It’s a pity! I think a conversation between creators of these comics and religious people who can stop to listen would be thought-provoking for both sides.

Comics creators are eager to dip into the already highly-charged conversation that religious subjects offer. Publishers are desperate for the new mediums that they can sell to new markets. They’ve finally discovered that women read their comics (and even write about them), now I submit that the vast number of people on the planet whose lives are somehow entangled with religion would love to read about these ideas in new, creative ways.